Final Fantasy is the David Bowie of JRPG franchises.

OK, I know that statement sounds ridiculous, but hear me out. David Bowie was, and still is, one of popular music's most beloved figures. Over the course of his six-decade career, Bowie reinvented himself endlessly — his 1967 debut was a competent yet somewhat plain album adjacent to The Rolling Stones, before he transformed himself into his alter ego Ziggy Stardust, a glam rock superstar who communes with alien lifeforms. After a dodgy flirtation with fascist imagery as The Thin White Duke, the late '70s saw Bowie partner with sound artist and Roxy Music alumnus Brian Eno to create his loose Berlin Trilogy, a trio of krautrock-influenced albums that delved into experimentalism while still remaining unabashedly pop. The '80s onward would see several more guises of the ever-shapeshifting Bowie; the yuppie-esque new wave of Let's Dance, a 1995 reunion with Eno for the angsty industrial Outside, borrowing from drum 'n' bass and techno in 1997 for Earthling, culminating in the haunting post-punk jazz of 2016's Blackstar, an album that can be interpreted as Bowie coming to terms with his own death.

Highly visible, proficient, and inspirational in his own right, Bowie was not wholly original. And yet, that wasn't his job — Bowie was a pop artist rather than a sound artist, and it was a role he excelled at. Bowie's entire oeuvre is unmistakably informed by artists who interested him, no matter the genre — The Velvet Underground, Roxy Music, Kraftwerk, Neu!, Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross, The Prodigy. It wasn't just music, either, as Bowie would borrow his visual aesthetics from sources such as pin-up photography, pulp science fiction, German Expressionism, and surrealism. But unoriginality is not shorthand for lazy or derivative — Bowie melded his influences to create a unique body of work that was very much his own.

I think you can see what I'm getting at here.

Final Fantasy's humble, 8-bit beginning in 1987 was a straight-laced competitor to Dragon Quest; a digital simulacrum of a by-the-numbers Dungeons & Dragons campaign. Its two sequels used this framework as a jumping off point to experiment with different ideas. Final Fantasy II was one of the more story-heavy JRPGs of its day: an evil Empire threatening the world, its pre-set protagonists with their own personalities, death, betrayal, twists and turns, not to mention its much-maligned yet unique skill-based progression system. Final Fantasy III dialed the story down to put the mechanics at the forefront, so as to experiment with a highly tactile job system.

The 16-bit era was just as varied as the trilogy that preceded it. Final Fantasy IV feels like a logical continuation of the narrative ideas seeded in II, as informed by Star Wars. Following IV's lead, Final Fantasy V borrows from III, expanding the job system and dialing the plot back even further to be a lighthearted and comical romp, a tacit refusal to let melodrama get in the way of its toybox of spells and skills. Then came Final Fantasy VI, arguably the crown jewel of this period, with its somber, Steampunk twist on the Evil Empire plotline — where, in a surprise upset, the villain succeeds at their attempt to end the world.

The 32-bit era saw the third Final Fantasy trilogy, and a startlingly different look for the series. Final Fantasy VII famously ditched the low-fantasy to create a Norse-tinged cyberpunk dystopia informed by the likes of Battle Angel Alita and William Gibson's Sprawl Trilogy. Final Fantasy VIII kept the postmodern setting, but reeled the science fiction in ever so slightly, giving players a salaried job and statistics tied to the junctioning of magical spells found in the world. Final Fantasy IX served as a 3D callback to the setting and design of the 8- and early 16-bit titles, though one that felt alive and lived in. It was a love letter to longtime fans that went well beyond fanservice.

After reaching peak popularity in the 1990s, the millennium saw Final Fantasy shapeshift rapidly over the next seventeen years: Final Fantasy XII is another love letter to Star Wars, while Final Fantasy XV is a love letter to the American highway system. And that's only the main series — shapeshifting continued in all directions in the form of ill-advised cinematic adaptations, anime series, genre-bending spin-offs, multiplayer series, sequels to sequels, and not one but two highly popular MMORPGs.

So I'm genuinely confused whenever I hear the argument that Final Fantasy should "return to its roots" — its roots are constant reinvention! We wouldn't have had so many memorable moments if it had "stayed true" to any one entry. As we can see above, Final Fantasy enthusiastically wades into experimentation, both mechanical and narrative, and its influences are all over the place. Though it never goes too far into niche ideas, in order to remain accessible and familiar to wider audiences, it is still a series that is content to completely reinvent itself with each successive entry. And it achieves great success doing so; Final Fantasy's tradition of un-tradition has given us the enduring, diverse, and unlikely sequence of V, VI, and VII back to back. One would be hard pressed to find a fan willing to trade this chronology for any alternative; the same can be said for Bowie fans and the motley sequence of Diamond Dogs, Young Americans, and Station to Station. Tactile transformation is a characteristic ritual of its own, and just as valuable as close adherence to the past.

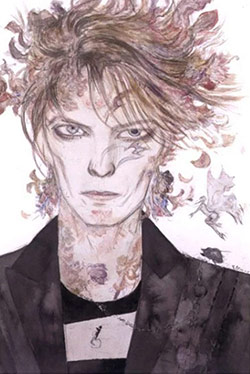

Editor's Note: We'd be remiss not to include the adorable David Bowie tribute that found its way into the game shortly after the artist's death: Above is the fight with Ziggy, as seen in The Antitower, a spriggan who floats on essentially a space rock, and whose signature attack is a group of more space rocks, each called Stardust. The Antitower's first boss, a giant frog, includes musical elements as well, with nods to, and lyrics from Kermit and The Muppets, so Ziggy fits not only thematically within the theme of this dungeon's bosses, but as Robert mentions here, within the entire history of Final Fantasy.

(Screencap from Mizzteq's excellent YouTube channel.)